Written by Zachary Fu

In the fourth quarter of a riveting basketball game, the home team head coach paces up and down the court sideline. A player on the bench, still in his warm-ups, sits in silence amidst the crowd’s deafening cheering. He tries to hide his frustration, but he is unable to camouflage his deep and evident desire to contribute to the game.

Any individual in the stands would be quick to label this player a “bench warmer,” or sometimes even just “the bench.” This collegiate player, however, is both the embodiment of hard work in grueling practices, and in many cases, a former high school star — details often overlooked when it’s down to the buzzer and all eyes are on the starting point guard taking the final shot.

Many players find themselves in this position — accepting the crowd’s applause after a victory without having broken a sweat in the last four quarters — yet only a select few have the character to respond with perseverance and positivity. Every one of them shares something deeper that drives them to push through hard circumstances: a dedication that goes beyond the love of the game. Without such dedication, no team would have a bench — and the bench is vital to any team’s victory. Without this player, the one still in his warm-ups, the team lacks the friction it needs to succeed.

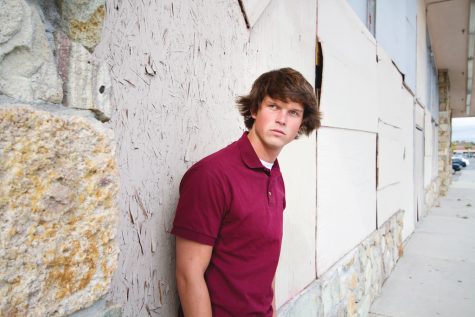

Senior point guard Elliot Tan is that player. As a senior in high school, the basketball court was his kingdom. He was captain of the Morrison High School basketball team in Taiwan, and led them to their league’s championship game. He also earned impressive individual accolades — including breaking the 1,000-point career scoring mark for his school and recording outstanding statistics with 25 points, six assists, nine rebounds, and three steals per game during that year. When he entered Biola in 2007, however, his role changed entirely. He went from being the player for whom the coach designates the game-winning shot to the player peering over the shoulders of his teammates in the huddle.

Tan worked hard and pushed himself in practices for two years, but still did not receive significant amounts of playing time. Many athletes who feel that they deserve more playing time simply transfer to different schools where they can be the stars of the team. Tan chose to stick it out — even if it meant fighting through the hardships of intense practices only to occupy the bench during games.

Although Tan doesn’t always contribute on the court during the games, he does all that he can to help the team perform.

“I just want my team to win,” he says. “A lot of it is working hard in practice, trying to do what I can to make the starters play better.”

Many people fail to realize that it is the bench players who scrimmage against the star players at practice. Without facing a challenge in these players, the starters would find it much harder to improve. Still, many question why a player would remain on a team without sharing a place in the spotlight.

“What drove me to stay on the team was just having the possibility to work hard and have the opportunity to play,” Tan says, adding that he has enjoyed being around his teammates and coaches every year. Simply having his name on the roster and the chance to earn any playing time at all, he says, is a chance many would love to have. “Sometimes when you’re in there at practice running lines, you forget that it’s a blessing to do that,” says Tan.

Other bench players include those who have proven themselves to be star collegiate athletes, but have been banished to the sidelines because of serious injuries. These players find themselves feeling totally helpless while they support their teams from off the field. As they watch from the sidelines, they itch to be released from the bondage of their crutches or arm slings.

Former Biola lacrosse player Jonathan McMahan tore the Anterior Cruciate Ligament (ACL) in his right knee during his freshman season, and then the ACL in his left knee the night before his junior season began. The rehabilitation process for torn ACLs differs in each case, but generally requires surgery and around 12 months to fully heal. For a collegiate athlete, this means a quarter of your career down the drain.

McMahan’s first injury occurred during the championship game of his freshman year. While racing toward the goal, he leaned his body into his defender, and took an awkward step with his right leg. The pain struck his body, eliciting his own screams as the lower half of his leg dug into the turf and the top half twisted over it — so intense that the goalie on the other side of the field heard the tear.

“You could hear the popping and cracking of everything in there tearing and it just gave out and I went down,” McMahan recalls. He underwent surgery for his knee in summer 2008, and the doctors prescribed him six months of physical therapy and six more months of avoiding contact sports, preventing McMahan from playing in his sophomore season. He seemed to be recovering just fine — returning to practice and getting voted team captain — until the second injury. McMahan tore his other ACL during a night practice before the team’s first season game. After a year of rigorous physical therapy and counting the days until he could play again, he was back to square one.

“I got overwhelmed,” says McMahan. McMahan struggled psychologically this time, battling depression for several weeks. For athletes, the real place of victory and defeat is often more in the mind than on the field. Psychological barriers can prove devastating to even the greatest player’s ability to perform. McMahan played a reserve role for the team in three games during that season, and coached as much as he could. It was the best he could do, but it was not enough to satisfy his hunger to play.

“I hated it,” McMahan says. “It’s hard to go from leader on the field to trying to coach and lead off the field. It’s amazing how things can change so fast and you’re not even expecting it.”

Like McMahan, freshman soccer player Allexa Mendoza also understands getting stuck on the sideline by injury. In her freshman season — the second game of her entire collegiate career — she suffered a tear in her right ACL. Ironically, she’d also torn her left ACL during her freshman year in high school. Like McMahan, Mendoza went through the same scenario twice. Since Mendoza received her second injury during her first year in college, instead of her last, she dealt with the psychological aspects at a much younger age than McMahan.

“My confidence level went down a lot,” she says. Prior to the injury, Mendoza was reaping the benefits of her hard work during pre-season, and her collegiate career was going better than she had expected. When she came to Biola, she had decided that she would be satisfied with even five minutes of playing time. She averaged twenty-two minutes of playing time in the few pre-season games she played before the injury; when her knee went out of commission, the average quickly dropped to zero.

“My confidence level went down a lot,” she says. Prior to the injury, Mendoza was reaping the benefits of her hard work during pre-season, and her collegiate career was going better than she had expected. When she came to Biola, she had decided that she would be satisfied with even five minutes of playing time. She averaged twenty-two minutes of playing time in the few pre-season games she played before the injury; when her knee went out of commission, the average quickly dropped to zero.

Like McMahan, Mendoza had surgery, and longed to support her team from the field as she watched from the bench.

“It was frustrating because I’d want to be in there … it was hard not being able to contribute,” she says. Instead of dwelling on her circumstances, however, Mendoza used her time to learn more about the game so that when she returns to the field next season, she will be better equipped to serve her team. She doesn’t just cheer from the bench, but also hones her attention to the play going on in front of her. She notices every pass, every run — the way the players move on and off the ball.

Many athletes, if not all of them, fear the public criticism and personal feelings of failure that are associated with anyone not listed in the starting lineup. Often, when athletes who are used to playing significant minutes face injury, they become apathetic and lose their passion for the game. Uninjured players who sit the bench can easily become jealous or embittered, putting up psychological barriers between themselves and the team. When either of these happens, the players’ attitude brings the team down and becomes a hindrance — the team loses not only a good player, but also a general spirit of confidence.

Tan, McMahan, and Mendoza have all worked to turn their mindsets away from themselves, and made efforts to restructure the way they contribute to their teams. Of course they desire to play, but they’ve all experienced the undeniable value of playing a different position — the one on the sideline.