Written by Katelynn Camp

John LaDue thought he would get expelled from Biola before he graduated. But he didn’t care. He’d rather be free to admit his identity as a gay man — even in the face of a community in complete opposition — than remain in the bonds of secrecy. Now, as a 30-year-old struggling to overcome same-sex attraction, LaDue sadly sees how far from freedom his homosexuality took him.

“It was like coming out of a closet and into a bird cage, from one bondage into another,” he says.

As a boy, LaDue didn’t live up to his father’s expectations. Finding more solace in drawing, painting and even making movies, he fell far short as the competitive athlete his father envisioned his eldest son would be.

His father’s disappointment made LaDue vulnerable to any form of affection. During his adolescence, with his sexual identity still forming, a man came to stay with LaDue’s family. The man offered, through sexual experimentation, the love that the young, naive LaDue longed for. This sexual encounter formed a same-sex attraction that consumed LaDue’s thoughts.

When LaDue arrived at Biola, he couldn’t handle his secret life any longer. A New York Times writer came to Biola and found out about LaDue’s sexual orientation. The juicy tidbit took up over 600 words of her published article, in which LaDue officially declared himself a gay man.

Though confused about his identity and defiantly screaming for acceptance, LaDue remembers Biola students who tried to reach out. But he also remembers hostility from both the school and outside communities. Several audience members booed LaDue when he received his undergraduate diploma in 2005. Faced with condemning Christians, he questioned his view of God. He had grown up as a missionary kid in Japan and had held an intimate relationship with God from a young age. LaDue wondered if the Church’s reaction was the same as God’s reaction. If so, then his perception of a loving and compassionate God would be shattered.

“I was really confused because I felt like I knew who God was, but then the Church in America reacted to this whole thing,” LaDue remembers. “[I thought] maybe my view of God is wrong, maybe I have too loose a view of God, maybe God was stricter than what I imagined.”

Today’s Church has come to a tipping point. Christians everywhere are facing the question of how to respond to homosexuality. On July 12, the leaders of the Episcopal Church officially declared their acceptance of gay bishops. Gary Strauss, a professor of psychology at Rosemead School of Psychology, who recently spoke at a local Episcopalian church’s forum on homosexuality, says he found it impossible to reconcile the two sides. A wide chasm exists between members who believe homosexuality is a sin and those who do not.

“These positions are sufficiently different and sufficiently opposed,” Strauss told the church. “I find no way to bridge [them] and that’s the dilemma that you face.” The choice to divide or reconcile isn’t exclusive to this Episcopalian church, and the answer isn’t clear. Strauss believes this local congregation’s plight portends a future division in the Church at large.

“My anticipation is that this issue of accepting-affirming gay lifestyle — the practice of same-sex activity within the Christian community — may become as divisive as the Reformation was when that occurred,” Strauss says.

The division in the Church originates from individual Christians’ reactions to homosexuality. Many people outside the Church think that Christians who believe homosexuality is a sin won’t love or accept homosexuals. Dr. Mark Saucy, a professor of theology at Talbot School of Theology, believes Christians share the blame for this condemnatory view.

“The only thing the world knows about us and homosexuality is that they think we hate homosexuals, and that’s a tragedy,” he says. “That we have made this ‘the special sin,’ I think that’s a tragedy. I think that’s inconsistent, and the finger of hypocrisy is rightly pointed our way.”

Pastor of Counseling at Mosaic Church in Pasadena David Auda — who draws from his own experience of human brokenness to complete the church’s mission statement of welcoming “people from all walks of life, regardless of where they are in their spiritual journey” — believes that even churches that do not officially bar entry to homosexuals can unconsciously create atmospheres that push them away.

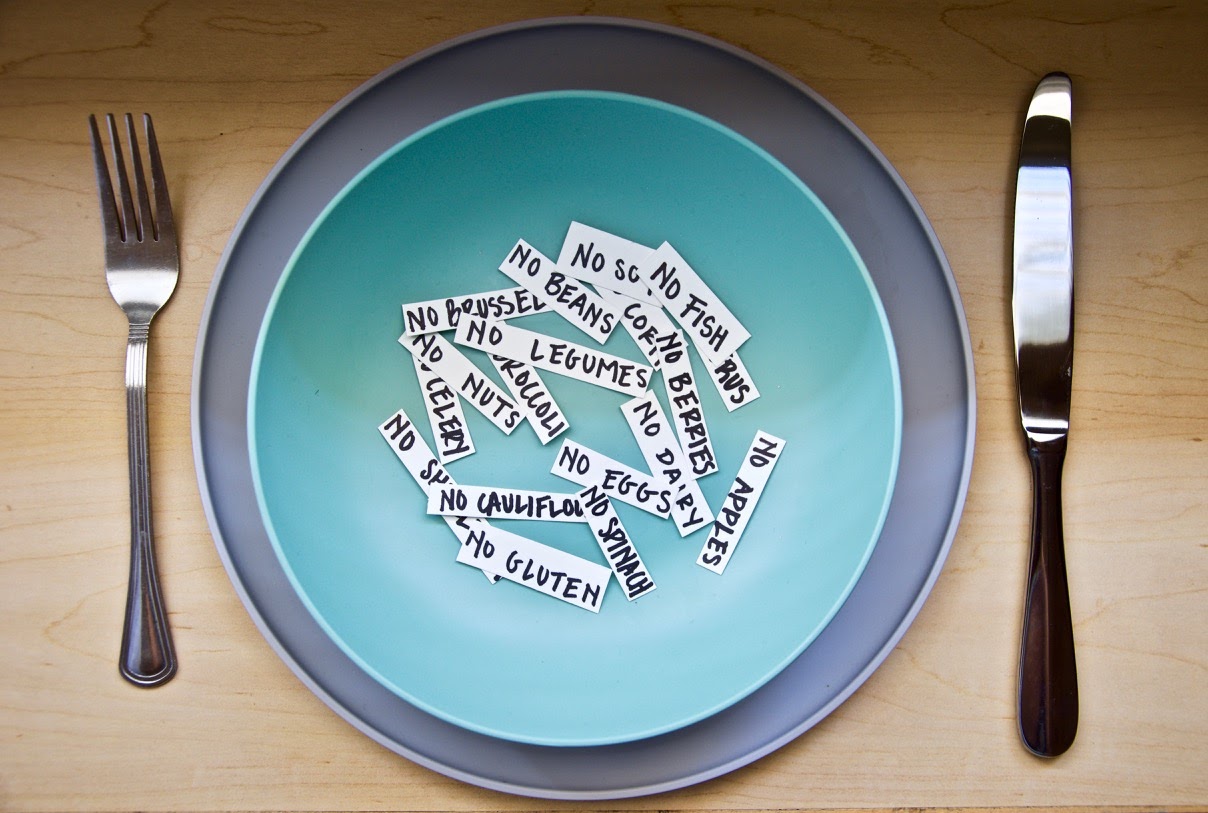

“I don’t know if we do it overtly, but we definitely do it subversively,” he explains. “We end up hanging mantels over the doorways of our churches and Christian clubs and basically let people know who’s invited and who’s not.”

The reputation for making homosexuality a “special sin,” or unintentionally barring homosexuals’ entry into church, can come from certain Christians’ harsh condemnation of homosexuals. Auda believes 1 Corinthians 6:9-11 — a passage often used to solely condemn homosexuality — serves specifically to curb Christians’ uncharitable judgment. In the passage, Paul lists the sins that will bar people from heaven, including “men who practice homosexuality” (ESV). Auda, however, focuses on the verses after the list in which Paul turns the table against those who pridefully think they are better than those dealing with the listed sins. Paul reminds them, “but such were some of you.” The implication is obvious to Auda: remember your own sin and understand that you cannot judge and condemn someone for sins you may or may not have committed in the past.

Scriptural interpretation lies at the heart of the argument of whether or not a Christian should accept and affirm homosexual lifestyles. Biola professors mainly teach a systematic view of interpreting Scripture. It’s not uncommon to see students lugging Wayne Grudem’s 1,300-page, hardbound A Systematic Theology to class on Biola’s campus; however, outside of Biola, some question systematic interpretation and focus on, what would Jesus do?

Jesus should stand at the center of the discussion on whether or not homosexuality is a sin, according to the Rev. Pat Langlois of Metropolitan Community Church Los Angeles, which has “a special and affirming outreach to gay, lesbian, bisexual and transgender people,” according to the church’s Web site.

“If being gay was that big of a deal with God, Jesus would have talked about it,” Langlois asserts.

Langlois, a lesbian pastor married to her partner of 10 years and mother of a two-year-old daughter, interprets Scripture by the standard of Jesus. While Langlois was dealing with certain problems in her life in her teenage years, she attended a Young Life youth group that told her about Jesus’ unconditional love. The message changed her life forever: she began to hope.

“It was all going to be okay,” Langlois remembers thinking, after reading Romans 8:28. “All the pain — it didn’t matter. God had a plan.”

Langlois’ experience in the Church changed, however, as she grew up. When she was in high school, Langlois attended a Catholic Church in which the priest, who had a prominent role in fostering Langlois’ love for Scripture, was eventually asked to step down because he was married. Langlois started questioning the Church because it began to contradict her view of Jesus as completely accepting and loving.

“Ironically, I stopped going to church because the authorities said who you could love and not love,” she says.

Langlois may have left the Church, but she did not throw away her love for God and His Word. Believing that Jesus would accept her no matter her sexual identity, she declared herself a lesbian.

Langlois now defends God’s acceptance of homosexual behavior from several years of Scriptural study. Her method of interpretation centers on Jesus.

“I look at it through the lens of Jesus,” she says. “I’ll go with what is centered in the foundation of Christ.”

Langlois believes Jesus’ healing of the Centurion guard’s servant in Luke 7 is an example of how Jesus didn’t condemn homosexuality. The word for “slave” in the passage, Langlois argues, is the word for “intimate lover,” or homosexual partner. Jesus’ response to the guard’s pleading for his servant’s healing didn’t condemn homosexuality.

“Jesus knew what that word meant,” Langlois says. “Jesus had the perfect opportunity to say, ‘You’re an abomination in the eyes of God, and he will die.’ But what did He say? ‘Your faith has healed him. Go back.’”

Langlois believes Christians should learn from this passage that they have no place to judge those immersed in a homosexual lifestyle.

“He [Jesus] went out of His way to reach out to the sexual minorities of His day — the ones who were born that way, made that way or chose to be that way,” she concludes.

Saucy, who interprets Scripture systematically, shares many of Langlois’ views against judging others but is firm about not supporting homosexuality. He hasn’t heard the translation of the term used for “slave” in Luke 7 to mean homosexual partner and doesn’t believe this to be credible. He also warns against anything that “separates the ‘red-letter’ Jesus from the commentary that Jesus’ inspired apostles give about him and his teaching.”

“We end up with a ‘Jesus only’ kind of ‘canon in the canon’ where only our preferred section alone is valid and trumps all the rest,” he says.

Saucy also points out that just because Jesus didn’t mention homosexuality doesn’t mean that He endorsed it — just because Jesus didn’t specifically mention incest or bestiality doesn’t mean He wasn’t against such acts, Saucy says.

He believes Jesus addresses homosexuality indirectly in Mark 10 when speaking on marriage.

“He says marriage — as an issue — is decided in Genesis,” Saucy explains. “He also says that God made them male and female, and so, God’s blessing of a gender different partnering Jesus does affirm too.”

Even with his belief that homosexuality is a sin according to Scripture, Auda believes God sees the sin but continues to love individuals who engage in it and recognizes them as His beloved.

“That’s why God’s paradigm is to love and forgive us and lead us into restoration rather than to condemn and crush us in order to somehow be righteously vindicated,” Auda says.

Auda believes homosexuality is simply another manifestation of human brokenness, which lies in one of three places: a fracture in a persons understanding of God, himself or his relationship with others. For Auda, when a person believes God wants to restore a relationship with him and then rectifies his view of himself, he can properly love those around him.

Auda saw how a distorted view of God leads to brokenness through struggling with his own identity as a young man. He dealt with the questions of who God was and who he himself was. Not satisfied with answers, Auda decided to live a hedonistic lifestyle. His life became a social chemistry lab as he experimented sexually, morally and ethically. The tipping point in the struggle came in a personal experience with God.

“God just grabbed me by the scruff of the neck and [said] ‘What are you doing and who are you?’”

Auda could not answer.

“At that point God, in His loving response, caused me to do a lot of soul-searching about who I really am, who He really is,” he says.

Auda found answers to his questions through the help of the Mosaic Church community, but he attributes his eventual restoration to the power of the Holy Spirit in his life.

LaDue, having gone through a similar struggle of identity, strongly agrees that God and God alone is the ultimate source of change in a person’s life.

“There’s no way we are going to logically walk a homosexual through the process to recovery,” LaDue says. “[Homosexuality is] a spiritual stronghold; there’s no way we’re going to do it without the Holy Spirit.”

LaDue did not come to this conclusion easily. For years, LaDue — like a despairing Job — demanded that God account for his struggle with homosexuality.

“My issue with God was: if you didn’t want me to be this way, then why am I this way?” he says. “And if you expect me not to live with homosexuality, why don’t you give me an option, a road to get out, to escape from it? Why? Why me? Why this?”

In the midst of LaDue’s soul-tearing struggle, he attended Biola-mandated counseling sessions once a week. The counselor consistently navigated LaDue back to the central issue of his struggle: refusing to see God as love. When LaDue responded by talking ecstatically about the new boyfriend in his life, the counselor never played judge. “Okay, you can go down that road,” LaDue’s counselor would say, “and if it doesn’t work out, come back to me. I’ll let you.”

The counselor never failed to show up the following week to listen, steaming mocha in hand, as LaDue tearfully explained his latest break up. The relationships didn’t satisfy. But his choice to continue in his homosexual lifestyle was deliberate.

Three years ago, years after graduating from Biola, LaDue decided to step away from homosexuality.

“I had to say, okay, the ‘why question’ is not going to be answered right now. I have to move forward. I have to decide that God … does have a good future in store for me,” LaDue says.

LaDue now lives in Japan, acting and filming while co-leading and playing worship for a local house church. Despite his decision, he still struggles to disentangle himself from same-sex attraction.

“Someday I’ll know why, but right now I need to let God be my daddy,” he concludes.

LaDue believes Christians need to be more like his counselor and willingly enter into non-condemning relationships with those suffering from sin’s enslavement. Strauss agrees with a similar vision but cautions against forming a relationship with someone simply to gain “a spiritual trophy.” A person knows and feels used when they are loved for a selfish end.

Strauss once invited Mark Haley, a former gay man now straight and married who spoke at Biola’s Torrey Conference in fall 2008, to speak in one of his classes. Haley gave several practical ways for Christians to re-form a proper image of Christ in the minds of those struggling with homosexuality.

“Love that person as you love any other person,” Haley said. “Don’t make this an elevated level of sin; this is a human manifestation of fallenness of which we all experience in one form or another.”

Auda believes local churches can help people struggling with homosexuality because they can present a right view of God. Auda’s conviction shows in his life today, as he counsels at Mosaic and uses the wisdom he gained through his struggles to help those who are dealing with brokenness. Auda passionately believes that healing comes through relationships.

“God knows our heart,” he says. “In the Church, we need to be at least close enough to people to know their heart before we put any kind of obstacle in front of them.” Auda’s eyes fill with tears of compassion, and his voice breaks. “We have to be close enough to them to know what their heart is.”

The similar suggestions of Haley, Strauss, Auda and LaDue comprise a fresh perspective on the issue of homosexuality. Rather than splitting Christians into two groups — those who do not accept homosexuals and those who do — the four men believe all Christians should accept a homosexual person as a human being, regardless of sin.

Auda believes local churches need to deal individually with people struggling with homosexuality. He wants churches to remember the example of Jesus who forgave the sin of many different people, on many separate occasions, with various responses and commands.

“I think that there can be a dynamic tension between ostracizing and fully giving a platform of advocacy for something,” Auda says. “And yet, if you ask me to define what that looks like in every church, in every community of faith, with every person, I can’t because Jesus dealt with it [sin] on a more immediate, personal reality.”