Written by Addi Freheit

The Attack

There is nothing unusual about the evening Noelle Axe sits down with her family for dinner. On the menu is a delicious spread of salmon, rice and salad— a meal her family has shared countless times before. And yet, nearly twenty minutes after eating, Axe texts her boyfriend to let him know that she is feeling unwell and cannot FaceTime him as she intended.

The burning begins in her stomach but spreads to her jaw and ears. The Benadryl does not ease the pain and in another twenty minutes, Axe’s jaw stiffens and locks up, her entire body breaks into red, angry hives and her lips rapidly swell. Axe is quickly rushed to Urgent Care, where she receives a steroid and Benadryl shot, intended to reduce the hives and swelling. Fearful that the ballooning of her lips indicates the fatal closing of her throat, Axe is then transferred to the emergency room. Meanwhile, the prescribed shots cause this nineteen-year-old girl to vomit unceasingly as her body attempts to defend itself from the food her body determined was poison.

Profiling the Enemy

Unfortunately, Axe’s experience is not unusual. Instances such as this one seem to be on the rise as adults’ bodies begin to reject food that was previously harmless. These reactions can come in a variety of forms, but are often categorized into either food sensitivities and intolerances or allergies.

An allergy is the body’s response against a foreign substance that enters into the bloodstream. This can result in either an acute reaction or a delayed response. During an acute response, the patient will “know that they have a reaction,” Dr. Dannelle Carlson, a naturopathic doctor at Evergreen Natural Healthcare in Washington, explains.

“So for example, you eat shrimp, your throat starts to close up, you know you’re allergic to shrimp,” Carlson said. “And most people don’t even want to further test that. It’s too risky.” An acute response, such as the one Axe experienced, is more clear and more dangerous than a delayed response, which can appear up to three days after the substance was consumed.

With a delayed response, it can be difficult to determine what the culprit is. A patient may consistently get headaches, but the correlation between those headaches and an allergy will not be clear if the reaction comes hours after ingestion. Whether the response is immediate or delayed and produces a stomach-ache or hives, an allergy will appear on a blood test.

A food sensitivity or intolerance, on the other hand, will not.

“The only way you can test a sensitivity is if you eliminate that food for four to six weeks… so your symptoms will either alleviate or go away,” said Carlson. After that period, a reintroduction of the food will make it apparent if it is the cause for the symptoms experienced.

Behind the Threat

Although gluten-free items were impossible to find twenty years ago, elimination diets have almost become a trend. A variety of soy-free, dairy-free, gluten-free foods can be found across the market. The reality is that many adults are not cutting out these items simply in the name of health, but because they have acquired an allergy or intolerance. Adults in their 30s and 40s are the second-most commonly treated of Carlson’s patients, following children ages five to 12.

One cannot help but question why? Why do so many adults appear to be acquiring allergies or food-intolerances toward foods that they were once able to eat every day?

Unfortunately, there is not a simple answer. Adults in their 30s and 40s are one of the first generations to use the microwave. As that convenient invention arrived, the working mom became a common reality, the fast-food industry exploded into a yellow-arched frenzy and processed meals were popularized in unforeseen proportions. A human’s stomach was not made to handle the repeated stress that comes with ingesting processed food.

Carlson calls this “total load.” When someone comes into contact with an allergen, their body will realize this but will not necessarily react. Even the next time the body interacts with this same food, it has the ability to shake it off. But every contact with that item still affects the gut. After repeated injuries, instances and an acquirement of stress, symptoms can either explode as they did in Noelle, or gradually get worse. The body can handle that stressor… until it cannot. That is when the body has reached its maximum capacity.

After reaching that capacity, an allergy and a food sensitivity can produce similar symptoms that affect the skin, joints, gastrointestinal region and the mind. These may include excessive gas, bloating, stomach pain, painful movement, headaches, fogginess, a rash or acne. Sometimes all the gut needs is time to heal. In other instances, time simply makes it clear just how poisonous that food is to the body.

Living Amidst the Enemy

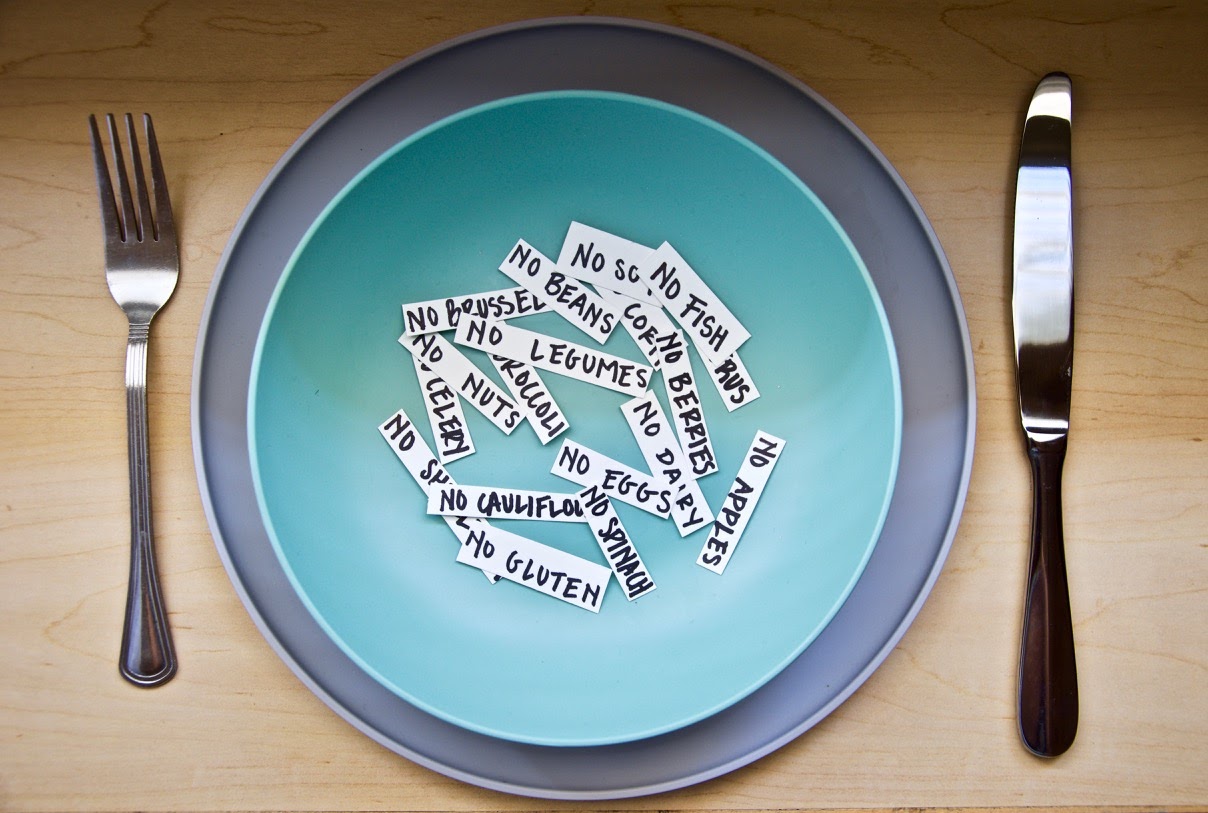

Practically and emotionally, living with an allergy is difficult. Freshman political science major Casey Jane Kuest and freshman intercultural studies major Brennan Lawrence know what it is like to navigate both allergies and food intolerances. Both have a large assortment of allergies and sensitivities that include gluten, dairy, soy, eggs, apples, peppers, blueberries, oats, almonds, potatoes, chicken, beef, beans, pork, cauliflower, peanuts, grapes, peas and corn… to name just a few.

It is undoubtedly challenging to find meals that fit within dietary restrictions as extensive as these, particularly when eating at restaurants, other people’s homes and in college.

“It’s so easy at home because we have all the recipes… But being at college is different because you don’t really have your own kitchen,” Kuest admits. Lawrence seconds this, saying that he eats the same thing every day.

Both students have a special diet meal plan at Biola University that enables them to plan their own meals. Neither Lawrence nor Kuest is unappreciative of the care that Biola takes to provide safe options for them; however, planning meals weeks in advance can be a lot of work for a college student. Kuest has obtained the help of her nutritionist to plan meals that are full of variety- an aspect that the average college student takes for granted when the entire cafeteria is at their disposal.

Eating out at restaurants and other people’s homes is another task altogether. As considerate as it is when someone offers to cater to their dietary restrictions, Lawrence and Kuest agree that it is often easier for them to simply bring their own food. Neither student wants someone to feel obligated to comply to their long list of foods-to-avoid, and cross-contamination is always an issue that few hosts know to consider.

Kuest admits that when visiting a restaurant she usually orders an assortment of sides to make a meal.

“You read the ingredients on a lot of things,” Lawrence says, explaining how he ensures that his food is allergy friendly. “You ask a lot, and you get good at knowing when someone has actually checked and when someone is just saying ‘oh, definitely.’”

The Loss

Lawrence says that the greatest loss brought on by his allergies and intolerances is not the food-restrictions themselves, but the loss of personal connection.

“It doesn’t feel the same to go to the same restaurant and eat different things [as] it does to make a meal together and eat the same things,” Lawrence explains. “You’re sharing an experience when you’re sharing a meal and it kind of opens you up to a deeper connection because we’re here together and we’re experiencing this together.”

Simply eating together is not the same as eating the same thing together. There is something sacred about sharing a meal with someone, and dietary-restrictions make this difficult to attain.

That being said, both Lawrence and Kuest rightfully consider the experience of sharing a meal with someone not worth the pain and discomfort it brings.

“If I’m eating certain things and I have a migraine all the time, I can’t fully engage with other people, I can’t concentrate on my work, I can’t sleep well, I can’t do any of these basic things that it means to be human,” Lawrence continues. “I love food, but no single food is worth ruining my ability to perform.”

Axe still does not know exactly which food was the culprit. Since then, she has acquired an EpiPen in the event that she has another reaction, but has primarily avoided everything she ate that night.

Luckily for all three of these students and others who deal with allergies and food sensitivities on a regular basis, there is a wider variety of options than there once was. Kuest remembers that when she was a kid the only milk-alternative was soy milk. Due to her allergies to dairy, soy, oats and almonds, she is only able to drink coconut milk. And Lawrence explains that his allergies have simply forced him to be creative.

“You can learn to like things,” he says, shrugging.

There is no denying the depth of difficulty that lies beneath allergies and food intolerances. The symptoms themselves are just as painful as the avoidance of certain foods and the emotions felt when denied the experience of a meal. As Axe, Kuest and Lawrence aptly proved, eating is about far more than simply fueling the body. A meal shared between friends and family is not something to be taken for granted.