Written by Bethany Miller

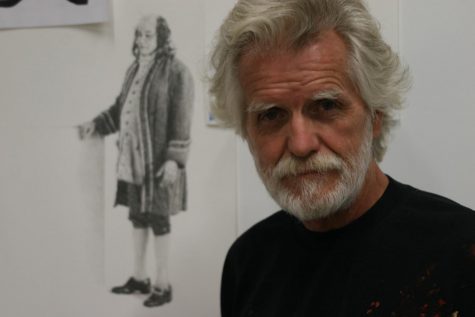

The 12-story building a few blocks outside of Skid Row seems, because of its age, that it must have stories to tell, but the blacked-out set of double-doors next door to Subway are nondescript. That’s why, when Kent Twitchell lets me in, my jaw nearly drops: Never, from those unassuming doors, would I have guessed that behind them was a cavernous studio space with enough paintings and sketches to fill a wing of the Getty Museum.

On the floor, there’s partly-finished portraits of John F. Kennedy and Ronald Reagan measuring easily 15 feet long; on one wall, sketches of the Founding Fathers, the Statue of Liberty, practice drawings of eyes; on the opposite wall, a giant painting of a hand, its index finger pointing forward (this is Michael Jackson’s hand, I’ll later learn); throughout the studio, bottles and cans of paint, books on theology and art history, old magazines and an endless variety of other art paraphernalia cover every horizontal surface. How many completed pieces of art the studio contains is anyone’s guess, but it’s obvious that Twitchell has at least half a dozen projects currently in the works.

“I always do things simultaneously so I don’t get bored,” he explains with a chuckle.

It seems unlikely that Twitchell, at age 69, has ever been bored in his life. Born and raised on a Michigan farm, he says he began drawing as soon as he could hold a pencil. Everyone around him immediately recognized his talent, though Twitchell did not take their compliments seriously at first.

“I just thought they were feeling sorry for me and trying to make me feel good,” he says. “I remember finally looking out the kitchen window and drawing the barn with texture and shading. It amazed me [that] it looked so real and everyone went crazy.”

From his early childhood through high school, Twitchell continued to pursue his newfound talent however he could — from sketching portraits of his teachers to decorating his friends’ cars to painting his school’s basketball court. Even the U.S. Air Force, which Twitchell joined after graduating from Everett High School, employed him as an illustrator while he was stationed in London.

During his time in the Air Force, Twitchell studied art at East Los Angeles College on the G.I. Bill. It was now the late 1960s, and the hippie movement, of which Twitchell considered himself a part, was in full swing. “We were painting on our shirts and on our vans, on our window shades — we were just painting everything to make it beautiful,” Twitchell says. “It was just about the world being beautiful. It wasn’t about anti-war until later.”

Initially, Twitchell participated in the psychedelic artwork that was popular at the time. He explains how these sorts of paintings gave rise to LA’s murals, and although he was competent at what he calls “abstract expressionism,” his passion was for realism.

Initially, Twitchell participated in the psychedelic artwork that was popular at the time. He explains how these sorts of paintings gave rise to LA’s murals, and although he was competent at what he calls “abstract expressionism,” his passion was for realism.

“Nothing was less fashionable then than realism,” he says. “And yet, that was who I really was.” In 1971, Twitchell opted to pursue his first love, and painted a strikingly lifelike portrait of actor Steve McQueen — his first of many large-scale murals — on the side of a friend’s childhood home in downtown LA.

Outside of the four-member troupe of artists who called themselves the Los Angeles Fine Arts Squad, Twitchell was the only artist in the world at the time creating realism-based street art. And when the Fine Arts Squad disbanded in 1974, Twitchell continued his work. The media, fascinated with the uniqueness of Twitchell’s projects, quickly made him a regular fixture in newspapers and broadcasts, although Twitchell jokes that most reporters only followed him because “they had nothing else to cover.”

He admits, however, that as a young man who had become something of an overnight sensation, he was not always so modest. He recalls one day from the late 1980s when a television camera crew had surrounded him as he worked on a mural alongside the 405 freeway. Suddenly, the reporters noticed a column of smoke in the distance.

“One of them said, ‘Look! There’s real news!’” Twitchell remembers with a laugh. “And I thought, ‘Oh, that’s right. I’m Mr. Slow News Day. . . Thank you, God, I needed that.’”

More than 30 years later, Twitchell may have grown far more humble, but his public recognition has continued to expand. He has created more than 100 murals across the country, and he is widely credited for earning Los Angeles recognition as the “mural capital of the world.”

Twitchell’s road to renown has not been without hardships. In 1994, his Sunset Boulevard studio of 18 years was destroyed in a magnitude 6.8 earthquake, and 10 years later, the studio he had moved to in Northern California flooded. Twitchell lost a number of studio pieces to both disasters, and those are not the only works he’s seen ruined: Several of his murals have been marred beyond recognition by graffiti or intentionally obliterated.

For the amount of time and painstaking attentiveness Twitchell puts into his art, he is far less possessive of his work than one might expect. “Take whatever pictures you want,” he tells the photographer who accompanied me to his studio. “It’s all public art as far as I’m concerned.”

He regards even the defacement of his earlier murals with the same composure. A portrait of artist Jim Morphesis that Twitchell painted along the 110 Freeway was tagged beyond recognition; a mural depicting runners in the LA Marathon was also vandalized; his first mural featuring Steve McQueen was completely painted over. Twitchell is understandably saddened by the harm done to these pieces — remarking wryly that Los Angeles has devolved into“the graffiti capital of the world” — and admits he has developed fonder feelings for indoor murals. In most cases, though, he takes his losses in stride, sometimes restoring or relocating pieces that had been particularly meaningful to him or to the community, but not seeking any retribution.

“I never sue anyone unless I’m lassoed into it by the art world,” he explains. The only such instances where Twitchell felt obligated to pursue litigation were when two of his most iconic murals — one an homage to his late grandmother overlooking the Hollywood Freeway, the other of local pop artist Ed Ruscha on the side of a government-owned building — were illegally painted over in 1987 and 2006, respectively.

“I’ve had other pieces painted out, and I don’t care,” Twitchell says. “But [the Ed Ruscha monument] had become sort of a symbol of street art in Los Angeles. It was just so public, and to just ignore it would have weakened [laws protecting artists’ moral rights].”  With a long career marked by critical acclaim and triumph in many forms, Twitchell has every right to self-importance, yet his demeanor is anything but egotistical. The pride he takes in his work is obvious, but it derives from a pure love of art, rather than from a sense of accomplishment.

With a long career marked by critical acclaim and triumph in many forms, Twitchell has every right to self-importance, yet his demeanor is anything but egotistical. The pride he takes in his work is obvious, but it derives from a pure love of art, rather than from a sense of accomplishment.

Presumably, Twitchell could afford to live in luxury; instead, he spends his nights in his studio, or in a condo he shares with his uncle. He’s well-connected enough that he could use any beautiful face as inspiration, but most often chooses his models based on their character or their histories. He has done his fair share of commissioned work, but created most of his pieces to honor people whom he admires.

At heart, it seems, Twitchell is still that simple Michigan farm boy, largely unaffected by the attention — both positive and negative — his work has attracted. Somewhat paradoxically, Twitchell credits his art for keeping him grounded and authentic. “Art is who I am,” he says. “Everything I’ve ever done has been who I am. I didn’t do what was fashionable; I did what mattered to me, because it was a lot more fun and a lot more rewarding, and that brought me back to who I was inside, which was a Christian.”

Twitchell says his faith is inextricably intertwined with his art, influencing every piece he creates. Biola’s Jesus mural, officially titled “The Word,” is his only overtly Christian piece, but most of his murals contain some religious allusion. For example, “The Freeway Lady” and a carpenter Twitchell featured in a mural at Otis College of Art and Design represent the Virgin Mary and Jesus, respectively. “I like people to look up at my monuments and see the clouds behind them and see [my subjects] as sacred beings set apart, created by God,” he says.

As Twitchell’s faith informs his art, his art, likewise, helps cultivate his faith in multiple ways. The time he spends working gives him the opportunity to listen to Bible studies or sermons on his iPhone, and he says that God has spoken to him both through the art itself and through the world’s response to it. And that, more than recognition, more than lawsuits, more than even his own passion, is what has defined his career.

“My mother always told me that one day I was going to be a big artist,” Twitchell remembers. “I was just this farm boy, very simple, and then suddenly one day people were knocking down my door who I’d seen on television. I knew it had to be that God was doing something.”

WEB EXTRA:

Some of Twitchell’s murals that remain in the area:

○ Steve McQueen (originally 1971, restored 2010), Union Avenue and 6th Street, Los Angeles

○ Strother Martin (1972), Fountain Avenue and Kingsley Drive, Los Angeles

○ Bride and Groom (1972), 240 South Broadway, Los Angeles

○ The Freeway Lady (originally 1974, relocated 1987), 13261 Moorpark St., Sherman Oaks

○ LA Marathon (originally 1990, restored 2006), 5 Freeway near exit 138 — Stadium Way

○ Harbor Freeway Overture (1991), Citicorp Plaza parking structure, 8th Street and 110 Freeway, Los Angeles