Written by Adrienne Nunley

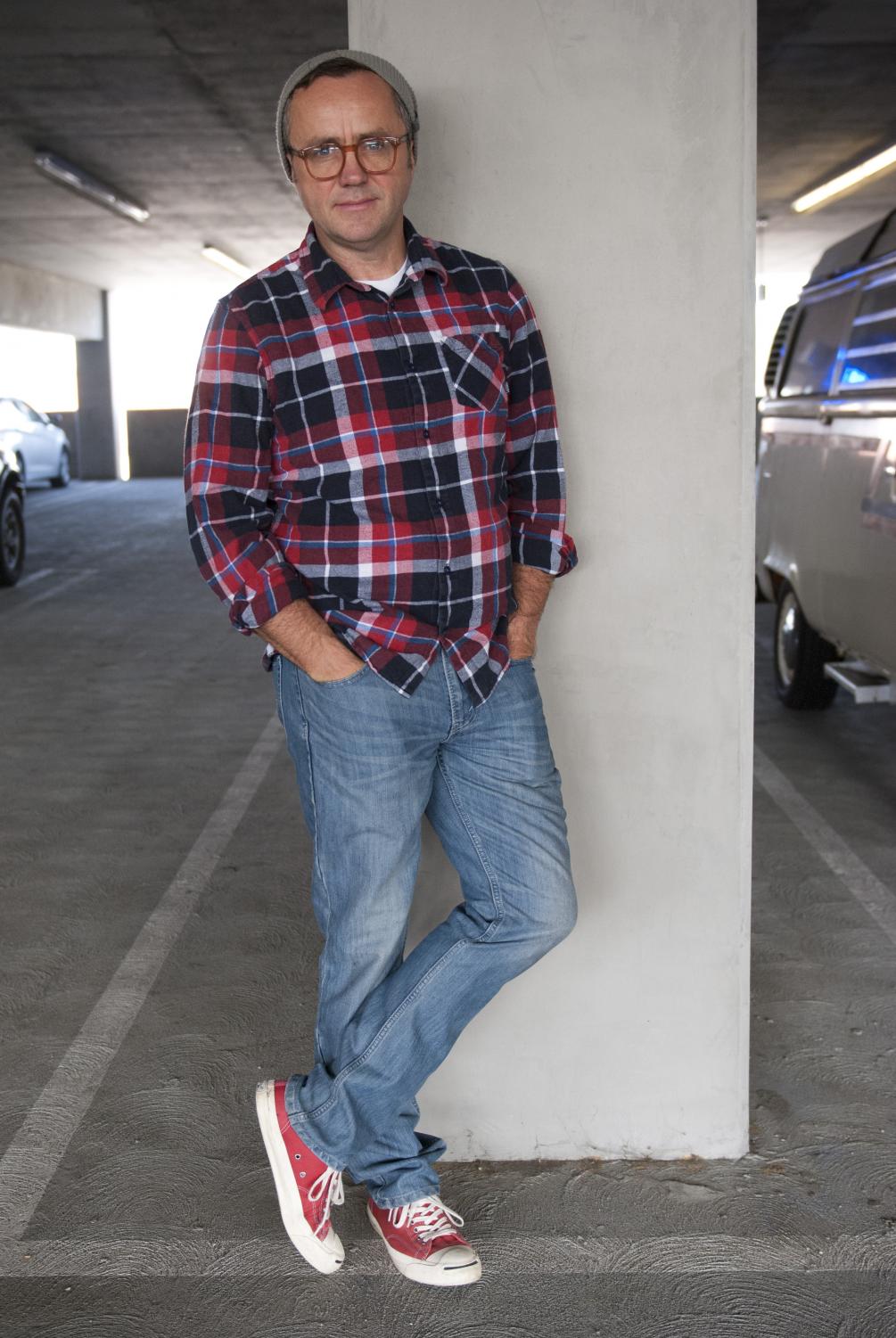

David Ottestad attended Biola in the fall semester of 2008 before he realized the American Dream wasn’t for him.

When the time came to make post-high school plans, Ottestad had no idea what he wanted to do. His parents encouraged him to pursue the four-year college experience, believing, like many American families, in the ability of a bachelor’s degree to ensure some sort of future security. Ottestad wasn’t interested, but he eventually decided on Biola after getting accepted into the film program.

In his first semester, Ottestad realized his true passion: music.

“Instead of studying,” Ottestad says, “I was writing music in every class.” He began reconsidering his original major, but worried about turning music — something he loved — into an assignment or an obligation.

In this same semester, however, Ottestad also realized that Biola was not the best place for him to pursue this passion. He withdrew from Biola and started his band, The Wandering Tree.

“I think for a lot of people, college is a great place to be,” Ottestad clarifies. “It’s a good place to define yourself and figure out what God has called you to do, but that wasn’t what it was like for me.”

Although Ottestad now feels more free, working in the music industry presents various challenges of its own.

“I wake up every day knowing I’m pursuing a dream, or an industry, that is completely broken,” Ottestad says. “I’ve always heard that the industry is really dark; there is no God.” Ottestad stresses the amount of manipulation that takes place in the music industry. A band will befriend another in order to tour with them and build up their own name. David realizes that the best way to avoid becoming consumed by such ambitions and to find real success is by not focusing on labels, managers, and producers. To combat this consumption, The Wandering Tree purposefully spends time meeting people and getting to know them. They learn names and listen to problems. “Once you put more focus on making those relationships, then it’s a more genuine and joyous experience,” Ottestad says.

While Ottestad enjoyed his time in the music industry, his parents continued to be wary. “Don’t you want to meet people in college?” David’s mother asked him after he left Biola. David feels that being in the band is his social experience. When the band goes back to a city where they’ve previously played, it excites him to see the people he met there before.

“I wouldn’t know these people or have these relationships if I hadn’t pursued this dream,” he says. It’s not monetary gains that determine their succes, but rather the growth of their fan base, the relationships they get to make, and the lives they get to influence.

“I don’t think the Bible really talks about success the way we’ve defined it,” Ottestad says. He feels that in America, success is commonly defined by money and academic standing. But for Ottestad, real success has nothing to do with money, and nothing to do with one’s self. Ottestad tries to align his vision of success with the Bible’s. “Anytime I consider myself successful,” Ottestad says, “is when I genuinely stop thinking about what brings me glory, and instead, what brings God glory.” He feels that in order to accomplish this, Americans need to stop thinking about money and personal reputations — contrary to the norm for most on the track to fame and fortune. They need to let go of part of “the dream.”

People like to dream — of happiness, of love, of success. Everyone’s dream looks a little different, yet a certain phrase has been used over the years and throughout the nation to describe them all: the American Dream.

This dream often includes spending four years at an esteemed university, getting married and raising the ideal family, owning a home, earning an annual six-digit income, and then retiring to the Bahamas. The American Dream embodies the way this country defines success. Aaron Kleist, department of English chair of humanities at Biola, sums up the dream as “a house with a white picket fence.”

What happens if someone doesn’t want a white picket fence? What happens if a person’s dreams don’t line up with this dream? What happens if life doesn’t go exactly as planned?

Cheryl Krake

Cheryl Krake was, like Ottestad, a student whose time at Biola was cut short. While Ottestad couldn’t wait to leave campus, Krake dreamed of having the four-year experience at Biola. She got accepted, enrolled, and was a student at Biola from Fall 2009 through Spring 2010. At the end of the summer 2010, however, Krake realized she wouldn’t be able to return to Biola due to financial limitations.

“I was in a mix of emotions,” Krake says. “It was a very… depressed time of, ‘Okay, my dreams are falling. God, what are you trying to teach me now? What are you trying to do with that?’”

Around that time, Krake received an internship at a church in Long Beach working with junior high students. Her family encouraged her to stick to that commitment even though she could not continue at Biola.

“Although the door to Biola closed,” Krake says, “another one opened.” The internship may not have been a part of her plans, but she thoroughly enjoys working with the junior high students.

“I love student ministries,” Krake says. “I’ve always wanted to work with young people, but [the internship] wasn’t the way I saw God using that [desire]. I’m learning so much about myself, and ministry, and ways to do ministry, just using the gifts that God has given me and being social.”

Along with interning, Krake currently attends Golden West College in Huntington Beach. Next year, she plans to take a year off from college to attend a cosmetology school. She hopes to eventually get a degree in business with an emphasis in marketing. Cheryl says that most people in the cosmetology industry use it as a back-up plan when their dreams don’t happen, but this is actually something she would enjoy doing for the rest of her life.

“People always define success as how much money you make,” Krake says. “I’ve always wanted the nicer things in life. I’m going into the music and fashion industry, doing hair and what not. People pay money for these things. I don’t want it to be about that, to be about the money. I want it to be about the relationships that I’m going to make.”

Krake says she doesn’t like the word “success” because it looks different for every person. For her, a successful day is one where, at the end of it, she can look back and say, “I did well, and God is good.” She considers her life a success if she’s doing something she enjoys and loves the people she’s around.

Krake enjoys working with her students and feels that part of her success comes from getting to actively love people all the time. Krake currently lives in an apartment complex where the majority of the residents are over 65 years old, and she really enjoys interacting with them.

“Every day, I realize that God has me where I’m at to bless the people around me,” she says, noting the importance of her interactions while doing small things like parking the car, checking the mail, and shopping for groceries.

“I love that my story is different,” she says. “I don’t like being like everyone else. I don’t like my life being defined by a dream, as some people would say. I like to shock people.”

Ann Marie Cortez

While Krake wasn’t afraid to defy common expectations, Ann Marie Cortez struggled with her decision to come to Biola. Cortez is a sophomore in the Torrey Honors Institute at Biola, majoring in communication studies with an interdisciplinary in political science. During her college search, her goal was to attend an Ivy League school, like Harvard or Yale, and then continue on to a law school. All her actions and decisions during high school were dedicated to this goal—she had the grades and accomplishments needed to make Harvard or Yale a reality.

“To everybody on the outside, it was a story wasted,” Cortez remembers. She recalls others saying things about her like: “She had so much potential and she went to Biola, of all places.” Cortez says she was constantly looked down on because of her decision.

Cortez says the circumstances surrounding her decision were hard because she was focused on what she could do to attain success, as opposed to where God might be directing her skills and talents.

“I was looking at success in the future versus success in the now,” Cortez says. “My only goal should be to be where God wants me in the moment. Not be somewhere were I want to be twenty years from now, and then go down the wrong path.”

Although Cortez does have goals of attending a renowned law school—such as Stanford Law or Pepperdine Law—and becoming a judge, she says that today she doesn’t define success in worldly terms. Instead, she suggests that it has more to do with serving God with her gifts and talents in every moment. Success, she says, doesn’t come down to who she becomes in regards to a career, but who she is as an individual. She feels she should not be motivated by money, position, or power. She asks herself, “Am I striving to be as Christ-like as I can be?”

God guided her to Biola, but Cortez was shaken by what came next. Two weeks into her freshman year at Biola, she received some distressing news. One of her closest friends from home had passed away. Cortez says it was incredibly difficult at the time, because she didn’t know anyone at Biola and she felt alone. She says that God used the circumstances to focus her reliance on him and the strangers he had put into her life at the time.

“It was like a kick-start to my community life, because I started friendships when I was in this very vulnerable state,” she says.

At first, she did not want to tell anyone what had happened, but she eventually poured everything out in one of her classes. She says the people God had placed around her prayed for her and comforted her during this difficult time.

“[This experience] forced me to be vulnerable with people and to open up to them and to lean on them, which is something that I’m not used to,” says Cortez, acknowledging her independence.

Through all of this, her mindset about college has changed. “[College] is not so much a way to reach an end, but it’s like a home and it’s a community,” says Cortez. “This is where I need to be and this is where I fit in.”

Aaron Kleist

Aaron Kleist was able to attend an Ivy League school, but that didn’t keep him from wrestling with the different ideas of success. One might say that his life coincides quite nicely with the American Dream: he holds a doctorate from the University of Cambridge in England, has accumulated countless awards and honors, contributed to many publications, and has a loving family. He’s had an adventurous life, having been raised on Saipan, Saudi Arabia, and Egypt. Despite all this, Kleist feels success should be defined by much more than earthly accomplishments.

Aaron Kleist was able to attend an Ivy League school, but that didn’t keep him from wrestling with the different ideas of success. One might say that his life coincides quite nicely with the American Dream: he holds a doctorate from the University of Cambridge in England, has accumulated countless awards and honors, contributed to many publications, and has a loving family. He’s had an adventurous life, having been raised on Saipan, Saudi Arabia, and Egypt. Despite all this, Kleist feels success should be defined by much more than earthly accomplishments.

“Say I am successful in all that I set out to do, and all my to-do lists I have ticked off, and at the end of my life, I look back and I have achieved success as this world would define it—whether that’s money or power or pleasure or respect, a name that lasts for some period of time, perhaps after my death, [or] it’s written in books,” Kleist says. “Ultimately, that is very small to a Sovereign God… for whom earth is a very small thing. He loves us, he cares about us, he values us, he knows us. But for him to stoop down to make us truly great by giving us a place in a story… that’s an astonishing and far larger measure of success.”

Kleist understands the personal longing to have our actions matter and be remembered. “In the Lord’s economy, there is the possibility of success that lasts—and that is large and real and true,” Kleist says. “I’m only going to get it if I’m willing to give up my own definition of what success looks like and accept his.”

Kleist has been in places — the halls of the greatest universities and conferences with some of the world’s greatest leaders — in which he was humbled by the number of “legitimate geniuses” he was working with. He has participated in lectures at the Second Annual Symposium on the Alfredian Boethius Project at Oxford University, and the Medieval Institute at the University of Fribourg in Switzerland. These experiences humbled him as he came to recognize his own areas of strength as well as his own areas of ineptness.

“[God] is able to use those small areas [of strength], and even the larger ones of ineptness, to do great things for his kingdom,” Kleist says. “He uses the foolish things of the world to shame the wise, the weak things to shame the strong… so that in the end, it’s obvious that if anything’s happened, it’s happened through him.”

Yet, most people still worry. So many, if not all, seem to wonder what they are meant to do and where they should go in the world. Even after taking a new perspective on success, it’s still easy to feel inadequate at figuring out the right path. Out of nowhere, things can drastically change — unplanned, unexpected things. Kleist admits the difficulties in making the right decisions, especially when it comes to making significant and deliberate transitions: signing a loan statement, accepting a job offer, stepping down from a current position.

“It’s painful! It’s extraordinarily painful.” In a culture of go-go-go and do-do-do, taking time to really consider how a certain opportunity will affect our lives can drive us crazy with impatience and anxiety. Kleist says that often times we will pray for God to lead us in a particular direction, and the response we get is silence. In spite of frustration, he sees a pattern of himself being more drawn to God through these experiences.

“The Lord uses the waiting for good in the end,” he says, noting that much personal strength and character gets built not by finally making such decisions, but in all the time of consideration and deliberation that leads up to them. “The waiting, the striving towards him, the seeking of the Lord, that’s a privilege and a gift and has a beauty in it and of itself.”

The White Picket Fence

The problem with the “white picket fence” of the American Dream is that it doesn’t let in the pain and the problems — the financial burdens that limit our options, the hidden passions we have that don’t match up with surrounding expectations, the gaps between the ideal and the real that haunt and hinder everyone in the nation.

Fortunately, this cookie-cutter version of success isn’t the only version of success. More fortunately, the other versions of success not only allow for, but often — if not always — include the surprises and struggles involved in finding our place and purpose in the world.

It can get hard when it seems like everyone around us is accomplishing all their goals. Even when we are able to take our eyes off the American Dream, the social pressures of a powerful and productive society can leave us feeling as if we’re getting left behind. The real American dream is that everyone has a different story to tell, so we shouldn’t let the picket fences keep us pent up in paralysis.

True success comes in figuring out what each of our stories looks like, a process that often involves the kind of waiting that Kleist speaks of. We will never be satisfied if we chase a dream that’s not our own, so the wait — however uncomfortable — is worth it. When all is said and done, we will each have a success story to tell. If the American Dream, white picket fences and all, gives us momentum towards that, then we should keep on dreaming.

photos by Beth Cissel and Jordan Nakamura