Written by Rachel Bicha

“But you’re a girl.”

“We just need some strong boys to help us move this table.”

“You’re so thin.”

“Have you gained weight?”

“You’re so emotional.”

“You’re so serious.”

“You seem angry. Are you on your period right now?”

“Have you found any boys yet at college? Are you dating someone?”

“So, tell me about your boyfriend. You are dating someone, right?”

“I think boys would be more interested if you weren’t so intimidating.”

“Are you sure you’re not gay?”

They say

words are less weighty

than sticks and stones but

I beg to differ.

Words

are

weighty.

They carry the weight of a dozen ideas.

The weight of a century of thought.

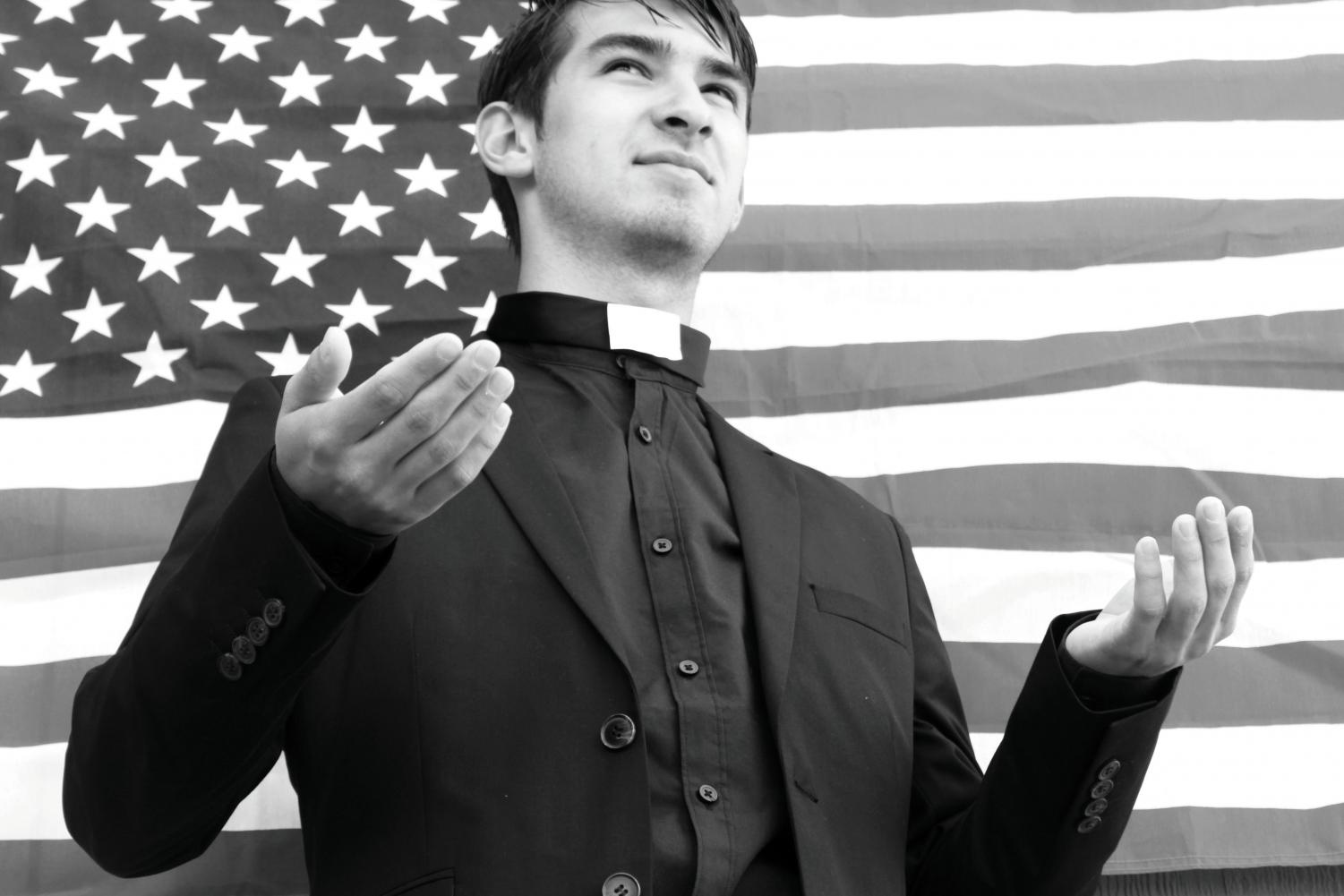

The weight of the expectations of a family, a church, a culture.

Words.

Words can remind us what we are

and tell us what we aren’t

what we’re expected to be

and don’t worry:

we’re already sizing ourselves up,

against expectations,

against advertising,

measuring ourselves against every other girl we see

in class, at Starbucks, in a magazine.

Oh sure,

you can tell us that magazine is photoshopped.

But don’t think that words

just words

can take away a hundred glossy photographs

of perfect eyes and perfect thighs.

We’re already comparing ourselves:

She’s so much prettier.

She’s so much smarter.

I’m too tall.

I’m too short.

I wear too much makeup.

I don’t wear enough makeup.

I’m too thin.

I’m too fat.

Words.

They float around in our head all day as we

stare and compare

and try to not to care

but we do

care.

Words

I’ve heard:

“We just need a few strong guys to help us move this table.”

Guess I missed that part where only boys could be strong, so I walked over. Two boys, already standing there, stared at fourth-grade me.

“They said boys.” One of them said.

“I can help.” I retorted. It was one of the white plastic tables every Sunday School classroom has, and I knew I could move it because I could pick up the mats at the gymnastics center that weighed even more, push them up onto my head and carry them across the room.

Both boys stared at me.

The teacher came over, and I waited for her to back me up. “Oh, you can go back to your group,” she said to me. “These boys can help me, you go ahead and go sit down.”

“But girls can’t do push-ups — and girl push-ups don’t count.”

When I was about ten or so, I was at my homeschool group, having recess, when some of the boys started challenging each other to push-up contests. One of the boys was a year or two older than me, and he was a swimmer, so he was beating everyone. My mom caught me watching them. “Well,” she said, “you gonna go beat ‘em?” I walked over and asked if I could join. A few of them rolled their eyes. “We’re having a contest and James is already beating everyone.”

“I can do push-ups.”

“Girl push-ups don’t count.” They retorted. I didn’t even know such a thing as “girl pushups” existed.

“I just do push-ups like this:” I said, and got down and did one.

“Fine.” They shrugged. “You go, James.” They set up counters for each of us.

Do I even need to mention that I won?

After that first victory, I realized that being able to do push-ups as a young girl was so unexpected and impressive that it became a little party trick, lined up in my back pocket like doing backflips or splits. I’d see a group of boys showing off to one another and ask innocently to join, then quickly knock out a long string of push-ups (or chin-ups or whatever it was) until I won and they were huffing and puffing and staring at me in awe and surprise. It thrilled my friends, and it gave me power in a sphere – both social and gendered – that I didn’t otherwise possess. Even the adults would be surprised and impressed. But this, too, had its limits.

Nothing terrible happened, no one horrific moment, but eventually I realized that my push-ups did not make me as strong as I had imagined: I was no longer fearless and unconquerable in the boyish realm, but I became aware of my tiny stature and realized I could be taken advantage of. My push-up prowess was gone, and I kept this in mind from then on.

In the end, feminism is not just for me, not just for you, not just for us. My interest in wanting – needing – to understand and study and express is not for myself, not entirely. It’s for my five-year-old niece who’s taking karate and can already chop a small board in half with her hand. It’s for one of my eight-year-old students who asked me if her tummy was too fat with her shirt. It’s for the nine-year-old on my childhood gymnastics team who was hospitalized for months for anorexia. It’s for the twelve-year-old who would spend hours plucking (with tweezers) every hair out of her legs because her mom wouldn’t let her shave and she was ashamed. It’s for the girl in high school who dropped out of AP Calculus because it was “all boys anyway.” It’s for my friends who have been sexually abused and assaulted. It’s for every girl who has been told, “but you’re a girl,” as if that is a limitation rather than a strength. It’s for every girl that’s been told – explicitly or not – that her body matters more than brains.

We don’t even need feminism now. I heard, and I believed for a time.

But we do.

We need it not just for women in the US, but for women around the world.

We need it because women need to know that they’re more than just skin and tendon.

We need it because women need to be valued for everything they have to contribute: brains, strength, compassion, kindness, courage, intellectual discovery.

We need it because walking to your car from the grocery store at 10pm shouldn’t feel unsafe. Because every woman knows not to leave the building without her keys already in hand, without already knowing where the car is parked, without having their keys interlaced between their fingertips, ready to strike if someone attacks.

We need it because I still get emails about sexual assault from campus safety, of assault that happen on this campus, on these streets, in this city.

We need it because I still get catcalled when I’m walking through town.

We need it because women from California to Calgary, Tajikistan to Turkey, New York to Nepal, and everywhere in between have not been able to believe that they are lovable, they are valuable, and they are enough.

so yes, we still need feminism.